The crisp air bites at your cheeks as you step onto the frozen lake, the sound of laughter and scraping metal echoing across the ice. This is the world of ice sledding, a tradition as old as winter itself, where simple wooden or metal sleds transform into vessels of speed and joy. From the rural ponds of Scandinavia to the bustling winter festivals of North America, ice sledding—or "ice sledges" as they’re sometimes called—has carved its place in cold-weather culture. But what is it about this seemingly rudimentary activity that continues to captivate generations?

At its core, ice sledding is a study in physics and friction. The smooth, polished runners of a sled glide effortlessly across the ice, a phenomenon that has fascinated scientists and enthusiasts alike. Unlike snow sledding, where the uneven texture of snow creates drag, ice offers near-frictionless movement. This allows sleds to reach surprising speeds with minimal effort, a thrill that has made ice sledding a favorite pastime in regions where lakes and rivers freeze solid for months at a time.

The history of ice sledding is as layered as the ice it’s performed on. Archaeological evidence suggests that early versions of sleds were used for transportation in icy regions as far back as 2000 BCE. Indigenous peoples in Siberia and North America crafted sleds from animal bones and hides, using them to traverse frozen landscapes long before the advent of modern winter sports. In Europe, ice sledding evolved into a leisure activity among the aristocracy during the Middle Ages, with ornate, decorated sleds becoming status symbols in cold-weather courts.

Modern ice sledding has taken on countless forms. In Russia, the "bobsleigh without brakes"—as ice sleds are sometimes called—remains a popular village sport, with daredevils racing down frozen rivers at breakneck speeds. The Dutch have elevated ice sledding to an art form, with the Elfstedentocht ice skating tour occasionally incorporating sledding elements when conditions allow. Meanwhile, in Canada and the northern United States, families gather on frozen lakes with everything from antique wooden sleds to repurposed plastic toboggans, proving that the activity requires no fancy equipment—just ice and enthusiasm.

Safety, of course, plays a crucial role in this deceptively simple sport. Every winter, emergency rooms see their share of ice sledding injuries, from minor bruises to more serious fractures. Experts emphasize checking ice thickness—at least 4 inches for walking and sledding—and avoiding areas near open water or moving currents. The positioning of the sledder matters too; lying flat reduces wind resistance but increases the risk of losing control, while sitting upright offers better visibility but may sacrifice speed. It’s this delicate balance between thrill and caution that defines the ice sledding experience.

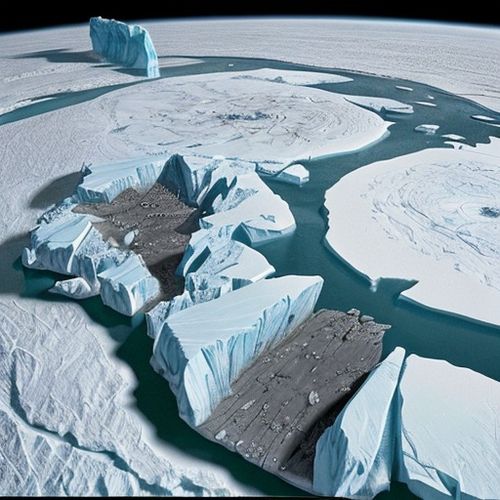

Climate change has begun altering the ice sledding landscape. Warmer winters mean shorter freezing periods for many traditionally icy regions, compressing the sledding season or eliminating it entirely in some areas. Paradoxically, some northern communities report thicker, more stable ice in certain years—a reminder of weather’s increasing volatility. This shift has led to innovations like artificial ice sledding tracks in winter sports complexes, though purists argue nothing replicates the authenticity of a natural frozen lake.

The cultural significance of ice sledding varies by region. In Finland, it’s intertwined with sauna culture—participants alternate between hot saunas and exhilarating sled runs in a practice believed to boost circulation. Japanese winter festivals feature elaborate ice sled courses illuminated by lanterns, turning the activity into a nighttime spectacle. Meanwhile, in alpine regions, ice sledding often follows a day of skiing, serving as a leisurely way to descend mountain villages as daylight fades.

Competitive ice sledding exists in niche circles. Informal races are common on frozen lakes worldwide, but organized events like the World Ice Sledding Championships (held intermittently in Switzerland) attract serious competitors. These races often feature custom-built sleds with precision-balanced runners and aerodynamic designs, a far cry from the improvised sleds of childhood. Some extreme versions involve sledding down icy mountain roads—a practice both thrilling and controversial due to its inherent dangers.

The future of ice sledding may lie in adaptation. As natural ice becomes less reliable in some regions, enthusiasts are exploring alternatives. Synthetic ice materials, initially developed for skating rinks, are being tested for sledding applications. Winter resorts are incorporating dedicated sledding hills with artificial cooling systems to guarantee seasons. Yet for all these innovations, the soul of ice sledding remains unchanged—the simple, primal joy of gliding across a frozen surface, propelled by nothing but gravity and momentum.

Perhaps what makes ice sledding endure is its democratic nature. Unlike many winter sports that require expensive gear or specialized training, ice sledding demands little more than something slippery and a slope. It connects us to our ancestors who first harnessed winter’s challenges for pleasure. In an age of digital entertainment and indoor comforts, the uncomplicated thrill of an ice sled reminds us of winter’s elemental joys—the bite of cold air, the sound of runners on ice, and the laughter that carries across frozen lakes.

By Emily Johnson/May 8, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/May 8, 2025

By Olivia Reed/May 8, 2025

By Lily Simpson/May 8, 2025

By Olivia Reed/May 8, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/May 8, 2025

By Daniel Scott/May 8, 2025

By George Bailey/May 8, 2025

By David Anderson/May 8, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/May 8, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/May 8, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 8, 2025

By Emily Johnson/May 8, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 8, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/May 8, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/May 8, 2025

By Noah Bell/May 8, 2025

By Lily Simpson/May 8, 2025

By Megan Clark/May 8, 2025

By Megan Clark/May 8, 2025